She had never liked other people’s furniture. It wasn’t their taste that concerned her, whether she liked what they chose or not. It was the spirit that they infused within the furniture.

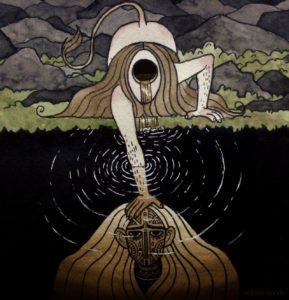

The way Gail saw it, every chair, every table, every bed – particularly every bed – had a life, had lived a life, and was a fount of thought and memory. She was not sure that she could live with the memories of others.

When Marcus said he needed to move away to write, she was disturbed.

‘Away where?’ she said.

‘You know,’ he said. ‘A cottage somewhere. Maybe by the sea or by a lake, somewhere I can see out across a landscape.’

‘You’ve got a landscape here. Why can’t you write here?’

‘It’s not a landscape,’ said Marcus. ‘It’s a garden.’

He saw this, she realised, as a question of location, while for her it was a question of the familiar versus the unfamiliar, the personal versus the impersonal. In her own home, the touch of her surroundings radiated through her body and gave her a sense of reassurance. She was safe among the memories she had created or inherited: her grandmother’s sideboard, her parents’ bed, the wardrobe she had had built by a local carpenter. As Gail moved about her home, she noted the slight shifts in the location of her furniture. She knew if her furniture was happy or sad. Sometimes she would be happy, but her furniture was sad. The furniture had a mind of its own.

When Marcus had moved into the shed at the bottom of the garden, she thought it strange but she accepted the strangeness, and so did her furniture. He was, after all, a writer and was allowed to diverge from the norm. But, clearly, he did not feel the mood of his immediate surroundings in the way that she did. His thoughts were taken up with the book that was due, the advance that had been paid, and the editor who would visit to ‘monitor’ his progress. He could, and should, be forgiven.

Viewing his behaviour from a distance, Gail would describe it to herself. And she imagined what her furniture would say about Marcus’s rejection of it. She committed these thoughts to paper, in an elegant hand, and using the ancient ballpoint that was once her father’s.

As Marcus sat in his shed, studying the daffodils, Gail sat in her kitchen listening to the words of her own characters, their anger, their sadness, their resentment. Why would Marcus want to distance himself? Were they, the table, the chairs, the cupboards not inspiration enough? And now he longed for the country and the furniture of others. The mood of the furniture turned from dismay to envy, envy of the unknown furniture of another home that was luring Marcus away. This, too, she wrote about as Marcus, in his limbo of the garden shed, wrote nothing at all.

With suitable reverence, Gail prepared a tray of tea and biscuits for the visitor – her mother’s teapot, the cups and saucers she had bought for one of her parents’ anniversaries, a tablecloth given to her by an aunt. The editor, phone in hand and wearied from an undesired but necessary journey across town, collapsed into her father’s favourite chair, and sat on the cushion sewn by her grandmother.

‘I’ll go and fetch Marcus,’ said Gail. ‘Try the biscuits. I made them myself.’ And with that, she set off down the garden path to alert Marcus to pause his writing and come up to the house. She found him texting, his screensaver scrolling motivational messages across his laptop.

‘All right?’ she said.

‘Yeah,’ said Marcus.

‘Jill’s here.’

‘Ok,’ he said, and sighed. ‘Be up in a minute.’

Re-entering the kitchen, Gail found Jill leaning up against the sink, reading from the notebook she had left on the table.

Jill looked up. Alert now, her eyes sparkled. ‘So, what’s this?’ she said.

© Janet Olearski

Janet Olearski is based in the United Arab Emirates. She is a graduate of the Manchester Writing School, and the founder of the Abu Dhabi Writers’ Workshop. Read more at: http://www.janetolearski.com